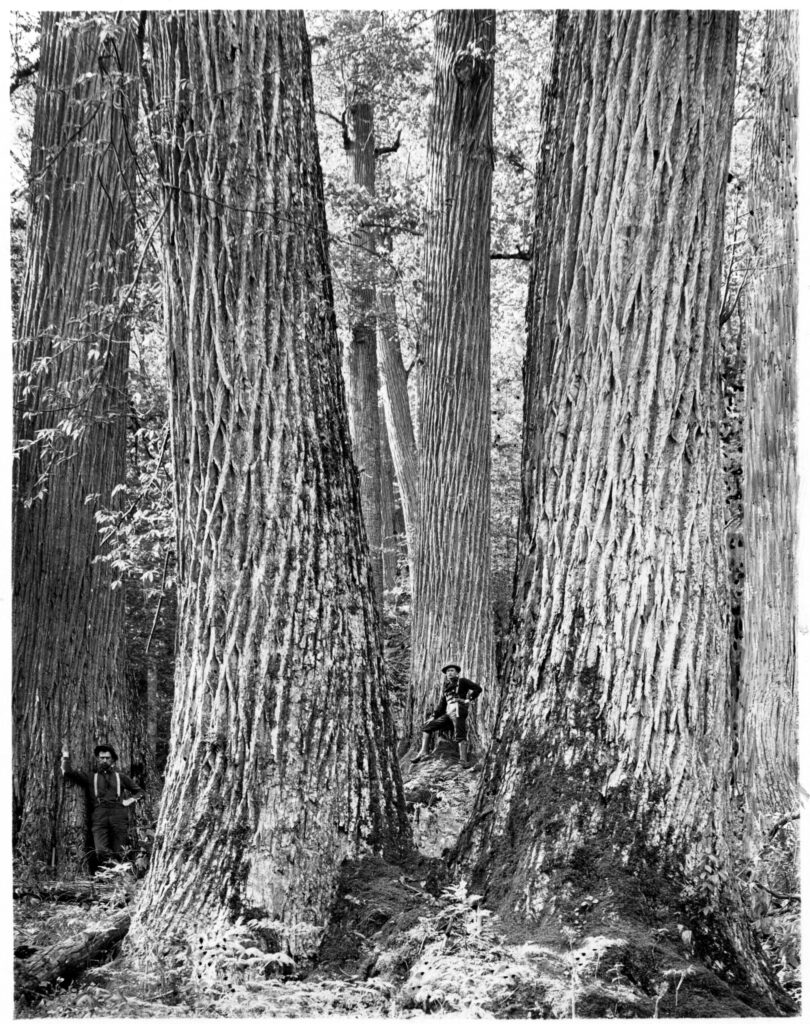

In fall of my sophomore year, I took Prof. Elaine Gan’s Multispecies Worldbuilding: The Chestnut Project, a multidisciplinary course that analyzed the technoscientific relationships between human and more-than-human entities, specifically focusing on the history of the American Chestnut. The American Chestnut used to be a cornerstone of American society — providing food, feed for animals, shade, and strong lumber that quite literally built the phone lines and log cabins of 19th and 20th century America.

Old-growth American Chestnuts circa 1909. Photo courtesy of the Forest History Society, Durham, NC

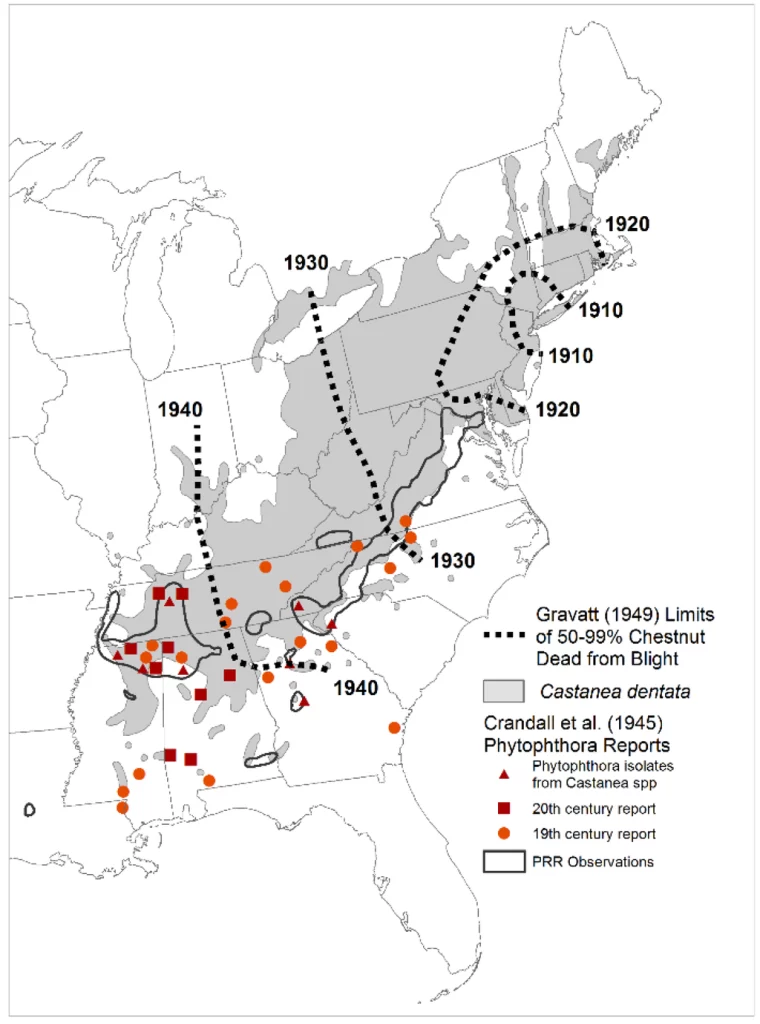

In the early 1900s, farmers and horticulturalists brought Japanese chestnuts to the Americas for cultivation and sale, but, unwittingly, brought a fungus blight to the states that completely decimated the entire American Chestnut population.

The way the Chestnut blight works is that it seeps into open “wounds” of the bark, and then begins constricting and consuming the tree. It brings the tree to the brink of death, but then keeps it alive so that it can continue to grow new branches for the fungus to absorb. Paradoxically, the fungus was better at ‘farming’ the American chestnut than we ever were – pointing holes in how humans generate our anthropocentric relationship to nature. If other species are more effective at farming resources that we use, how can we look to these more-than-human ways of being to better understand and situate ourselves in the world? The class also explored the scientific push to genetically engineer saplings of the American chestnut to be resistant to the blight, allowing for the tree to be proliferated, rewilded across the world.

This was an extremely influential class for me, with the readings and concepts informing much of the work I’ve engaged in since. You can read my thoughts on Mbembe’s Necropolitics or Haraway’s Situated Knowledge in my annotated bibliography, and it’s here where I was introduced to Matthews’ Landscapes and Throughscapes. My final paper used Matthew’s Landscapes and Throughscapes to construct a throughscape of Wesleyan, comparing how the administration treats and manages the ecology of our campus to other ways of managing ecology. I interviewed the head of Wesleyan’s WILD WES, the student-run permaculture garden on campus, and compared their philosophy to the ecological philosophy of the university.

A project I consider to be a partner to this one is the final project to my Introduction to Time-Based Media class, where we learned how to explore, reformat and transform the internet, as well as other forms of media, into video art. My final video, titled Universe/ University includes the interview with the head of WILD WES, as well as quotes from a variety of thinkers who theorized the position of the university in the world.

Leave a Reply